It’s been a while since I’ve been compelled to write a personal non-running post and Trump’s hyperactive reign as president has made me weary about where America is headed. There isn’t a lot I can do from this side of the planet except share (online and IRL). This blog turns FIVE this month so now is as good a time as any to tell the Bambi story.

My father was one of many Lebanese teens who traveled to the States in the early 80s, in the midst of the Lebanese Civil War. Dad ranked 4th in his promotion, like all Lebanese parents claim to have done, and took intensive English classes upon arrival in the land of the free. He enrolled in community colleges, eventually in a California state school, and was studying to be an electrical engineer. He met my Protestant blonde mommy “at a disco,” as they say. After a few months, some songs left on answering machines, and a wedding in Las Vegas, my parents were wed before either of them had hit 24. Baba was still a masters student at the time and had planned on working for NASA’s JPL but alas, we make plans and Allah laughs.

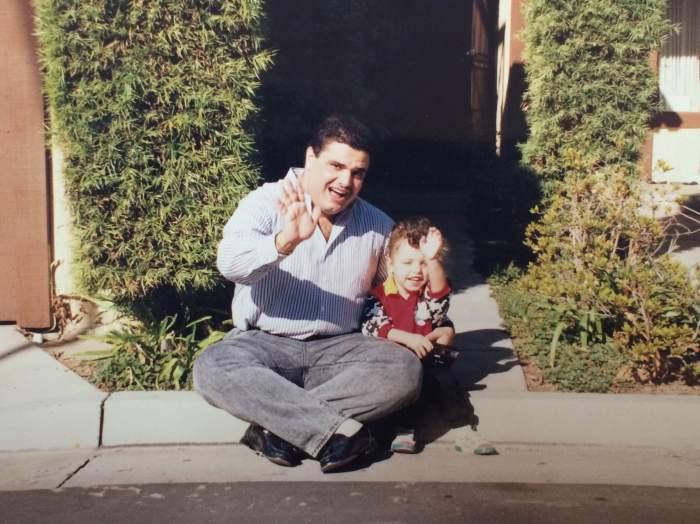

AND THEN I CAME ALONG

When I was a curly-haired munchkin growing up in Southern California, you could probably say that I identified as white. I went to private elementary schools that encouraged acceptance. My mom told me Bible bedtime stories, we celebrated every holiday, and dad told me Imam Ali words of wisdom. I attended a public middle school in a rich school district of an artsy gay-friendly town where 6th graders were taught about major religions and their core structures. If anything, I learned more about Islam from that history class than from my own Muslim dad. My mother’s family, technically white, was also full of mixed heritages due to my uncles and aunts marrying into every background and minority. My point is, I grew up in an environment that fostered tolerance and education but I also kinda grew up white. I didn’t know I was different because I hadn’t discovered that part of my identity. If anything, I had rejected it because Lebanon was still that tiny place where teta lived which sometimes had electricity but always had humidity (some things never change).

It wasn’t until I had moved to Lebanon at the formative age of 13, that I realized my Arab genes rendered me as an ethnic caucasian. Although white is an ethnicity, when anything is described as “ethnic,” it means it’s anything that isn’t white. It was only after I embraced my third-culture kid upbringing that I saw that my olive skin and dark features meant I was not white, that I was going to forever walk the tightrope of dual nationality and the respective stereotypes that each one came with.

After 9/11, being Arab became even more pronounced in my sense of who I was especially when it was stigmatized and automatically linked to terrorism. Instead of wanting to shy away from that part of me, I wanted to hold on tighter and make it known what being an Arab really meant, what living in Lebanon was actually like, and coming to terms with what being an Arab-American citizen allowed for me but not for others.

During the summer after graduating from high school, I had my first taste of violence due to a 34-day war with Israel. My family and I were displaced and we lost our home. The bombings that started with Rafik Hariri’s assassination, the invasions in neighboring countries, our deaths that were somewhat dismissed globally. All these events revealed a disheartening reality that your worth as a human, at least according to the media and the West, was very dependent on geography. Acts of terror in both my nations would repeatedly show me who I was in relation to the rest of the world.

BEING CHRUSLIM IN LEBANON

A friend of mine, also a product of a mixed marriage, had introduced me to this term which I thought was a perfect moniker for a situation that most can’t relate to. It also made my answer to, so what are you? take on an approachable tone. It made it easy for me to talk about and it made it easy for people to feel like they could ask for more. I love that I have a moral compass that was constructed from being exposed to two religions. I can understand both without being tied to a strict system of beliefs and although I would not say that I’m a particularly religious person, I’m principled in how I approach life while being accepting of others’ different approaches.

Living in Lebanon where religion is very present (too present some would argue), also pushed this appreciation for my mixed background further because I was able to blend in easily regardless of what sect someone identified with. The generalized misconception is that kids grow up confused not knowing what to believe in. In my case though, I grew up looking at religion as a source of guiding comfort for all rather than another source of division for the few.

AS A WOMAN IN THE MIDDLE EAST

In a household of 3 girls, we were empowered by our parents. Being a woman was never portrayed as a disadvantage. We were told that the world would treat us differently and that society would have unfair expectations of us because we were female. But we were also told that our gender should never be a factor that should keep us from being everything we wanted to be. Dad pushed us to be no-bullshit, no-drama girls who can do anything a boy can do. Mom showed us how to do it with compassion and patience.

I’ve been influenced by examples of sister strength throughout my young adult life. My education track exposed me to some of the most fierce ladies in the country. With all the top researchers of my pre-med days in AUB being female to the best design professors also being tough XX-chromosome cookies. From Dr. Nada Sinno of AUB’s bio department to Dr. Yasmine Taan, the woman responsible for bringing design to LAU, I was not under the impression that women couldn’t do it all.

This only continued as I entered the workforce. From my part-time job at LAU’s communications office which was 90% female to Leo Burnett Beirut where I worked on a 100% female team of 5 rockstar creatives led by Yasmina Baz, I had an ecosystem that made me forget about glass ceilings. When I had asked around about her, Yasmina had been described to me as the creative director with a Midas touch because everything she was involved in turned to gold. She showed me how to be meticulous with your work and confident with your ideas. She knew how to be firm yet kind. My second boss there, Betty Francis, a regional hair care guru, put life’s priorities into perspective and taught me self-respect in how you conduct yourself with others. I’d never imagined that advertising was still a MadMen’s world because of all the badass talent I had been surrounded with during my time at Leo. Burnett’s Beirut office is loaded with strong female role models in an international industry that is a male-dominated scene. On top of that, both my ladybosses taught me that you don’t have to choose one or the other, that the working mom wasn’t a myth of the Western workaholic world. You could climb the corporate ladder, find your person, and build something worth working for: a family.

AMERICA IN BEIRUT

I joke that the family empire I’m involved in now is a reflection of my parents’ marriage: bridging the worlds that they are each part of and fueling both economies while injecting food into whatever we do. I know that my experiences are mine alone and that average immigrant offspring have not lived my life but Lebanon has shown me that being exposed to diversity is a necessity while America has shown me what diversity can do in a nurturing environment. America’s mixture, not just of foreign doctors and scholars, but of average Joes and blue collar workers from all over is why, to the rest of the world, the USA represents possibility. Immigrants, whether refugee or not, are people looking for opportunity to succeed. One may arrive to start a falafel chain and another may become an engineer, marry a blonde lady, and sell beef jerky for a living after returning to the homeland. In the end, all immigrants are survivors, whether they’re fighting to stay alive or fighting to live with dignity. They are all people with stories to tell.

Their wedding photo is a Polaroid.

I’m proud of my nationalities and my parents because they shaped me into a tolerant, determined individual who just happens to be female. I love that the American ideals are being defended but I wish this fury was around when US foreign policy had been affecting these same banned (and unbanned) populations on their own soil. Perhaps the only positive effect that has resulted from Trump’s presidency is that the public are now scrutinizing every action being taken and order being made. There is a thirst for truth and knowledge that is unlike the complacency that was the status quo of late. As Jon Stewart said, maybe Trump will make America great again but not in the way he thought he would. He’ll make it great again by showing that Americans will stand by our pledge of allegiance that we recited to the stars & stripes every morning: one Nation under God, indivisible, with liberty and justice for all.

Beautiful

❤

Lovely story Farrah ❤ That polaroid photo of your parents' wedding is just perfect!

Thank you! And I agree, they’re adorbz hahaha

Pingback: Lebanon, I’m Leaving You for LA | Bambi's Soapbox